Those who missed Part 1 of this article, can read it 👉here. I strongly suggest you read it before continuing with this article.

Modern Parallels: Energy Flow and Scientific Attempts to Research Ki

Ki may sound mystical to some, but modern perspectives and many studies offer intriguing parallels to this age-old concept. Even though it is a concept we mostly encounter in eastern philosophy, I believe there are traces of it in ancient western cultures as well.

The idea of a life force was commonly connected to breath, spirit, or divine power in ancient societies. The term "Ka" and “Kivit” was used by the ancient Egyptians to describe a vital essence that supported life and served as a person's spiritual double. Aristotle and Plato investigated the idea of a world soul, or “Anima Mundi”, as the unifying force of nature. The Stoics in ancient Greece (and also Aristotle) developed the concept of “Pneuma”, a universal breath that pervades all existence. Similar ideas were adopted by the Romans, who used the term “Spiritus” to refer to both breath and an animating principle.

Also, in the centuries following the Renaissance, many other individuals in the West explored this concept. Henri Bergson in 1907 talked about the Élan vital. Carl Reichenbach about the Odic Force, Franz Mesmer about Mesmerism, and in the 20th century, psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich introduced the idea of “streamings”, representing a flow of bio-energy in the human body. He also called it Orgone. According to Reich’s theory, when a person is free of neurosis, optimistic and relaxed, energy streams freely, producing a feeling of inner glow and confidence, but when a person is anxious, repressed, or negative, these streamings get “dammed up,” causing tension and fatigue.

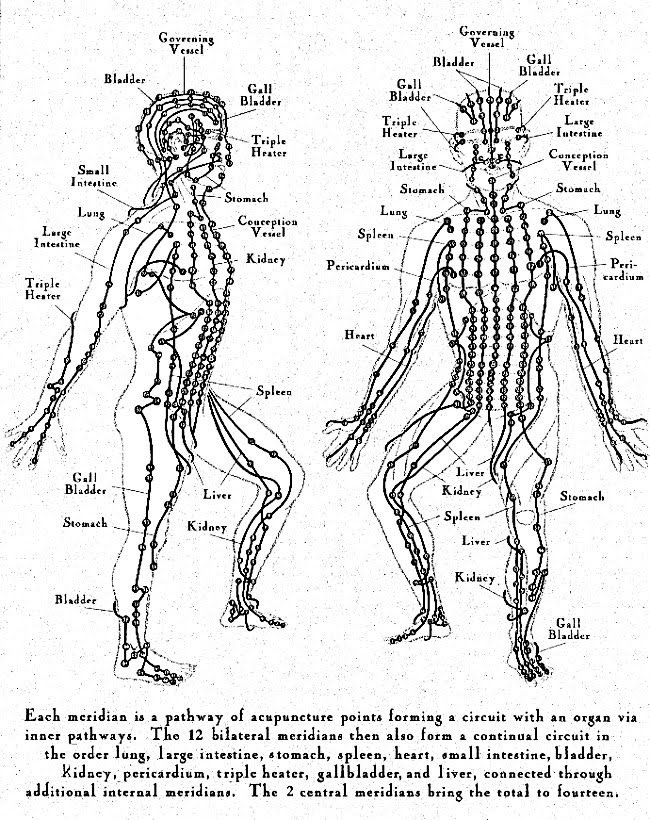

This is remarkably similar to the Eastern idea that positive thoughts let Ki flow, whereas fear or stress blocks Ki. Reich’s “streamings” might be seen as an early Western attempt to describe Ki in physiological terms. In other words, free-flowing inner energy correlates with vigor and wellbeing, while blocked energy correlates with discomfort and weakness, a notion shared by Ki-based healing arts like Acupuncture or Qigong.

Modern science has also begun to validate aspects of the Ki concept. A research project at M.I.T. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) in the late 1970s found evidence that “there actually is an electrical energy field around the human body, and it can be regulated… by breathing in a particular way.”

In fact, breathing exercises were shown to thicken or intensify this energy field, and some martial artists trained in Ki breathing had measurably different fields than average people. Beyond martial feats, the biofield concept of Ki has parallels in healing and psychology. Kirlian photographs of living organisms show colorful auras, which some interpret as life-force images (though empiric science attributes it to moisture and electromagnetism). Still, to this day, western medicine is exploring energy therapies: for example, devices that use electrical stimulation to promote tissue healing, akin to how Chinese Qigong (and Japanese Reiki) healers direct Ki to sick patients.

All these examples mirror the ancient intuition that an unseen energy sustains life and can be harnessed. While mainstream science doesn’t fully endorse concepts like Ki or aura, it does acknowledge that the body emits electromagnetic fields (for instance, the heart and brain produce measurable fields). The warrior’s practices – deep breathing, concentration, posture – can be seen as ways to optimize the body’s natural energy systems (better oxygenation, nerve signaling, etc.), thus producing very tangible effects. The M.I.T. study essentially confirmed that “Easterners regulate the body’s energy field by breathing”, and that disciplined breath control can amplify one’s bodily energy.

It seems like what the ancient intuitively (and perhaps not only) knew, science is beginning to confirm. It makes no sense to see Ki as magic, but rather, as a combination of subtle energies and psychophysical states. When harnessed, it can boost strength, resilience, and even extend one’s influence beyond the flesh. By studying both ancient insight and modern clues, we can proceed to deepen and experiment with our own understanding of Ki.

Naiki: The Samurai Doctrine of Mind and Energy Control

The samurai of Japan were deeply aware that victory in combat depended on more than physical strength. It depended also on spiritual energy and mental control. They had a concept called Naiki (Inner Ki), which can be described as the warrior’s doctrine of cultivating internal energy and mind.

In training, samurai learned that Mind (Shin), Energy (Ki), and Power (Ryoku) are connected. One manual summarizes this as a formula:

“Shin makes Ki, Ki makes Ryoku.”

In other words: “Your frame of mind or attitude (Shin) impacts your vital energy (Ki), which in turn generates a force (a strength) coming out from you that affects other people (ryoku). They always go together.”

If your mindset is strong and focused, your Ki will be strong, and if your Ki is strong, the power you exert (physically and psychologically) will be formidable. On the other hand, if the mind is weak or wavering, Ki falters and one’s outward power collapses.

Shin is psychological, Ki is psycho-physical, and Ryoku is physical.

It is a continuous chain from the invisible thought to the visible deed, or from the Metaphysical to the Physical. But I mentioned before, empiric science can only measure the physical. And it tends not to see it as an effect caused by a metaphysical factor. Who can blame them? 😂

Jokes aside, this principle - Shin-Ki-Ryoku- is at the heart of Naiki. Samurai would train their mind to be calm, bold, and clear (good shin), which would in turn fill their body with vigorous energy (strong ki), and finally translate into effective action (full ryoku). The 17th-century swordsman Yagyū Munenori described this interplay in terms of

“mind moved, energy moves; energy moved, technique follows.”

Thus, Ki has the ability to connect the body, mind, and action into one.

Practically, Naiki meant also inner mastery. Samurai practiced meditation and breathing techniques to control their thoughts and emotions under pressure, thereby regulating their Ki. They knew that an agitated mind could sabotage their sword arm:

“If your mind is preoccupied, your ki tenses, and you become awkward,”

warns one martial teaching. A centered mind, on the other hand, produces flexible, powerful Ki that can respond effortlessly. The legendary archers and swordsmen were said to move with an almost supernatural poise, but in truth, they had learned to unify mind and energy. A famous anecdote tells of an old archery master, Kenran Umeji. He would draw a heavy bow to full extension (a bow none but he could draw) and invite students to feel his arms: they were completely relaxed, without strain. He laughed and said,

“Only beginners use muscle power, I draw simply with the spirit,”

meaning he drew using Ki centered in the “hara” (abdomen) rather than brute force.

Rather than relying solely on muscular effort, his exceptional strength was derived from an internal concentration of Ki. This tale demonstrates Naiki in action: the master had learned to effectively channel his energy efficiently through breath and mental focus, obtaining maximum power with minimal physical tension.

The Naiki doctrine also taught the samurai how to maintain morale and willpower. A warrior facing overwhelming odds might normally feel fear, draining his Ki. But by understanding “Mind makes energy,” he could intentionally adopt a fearless attitude, literally “psyching himself up”, to keep his Ki strong.

In many Dōjō-s (training halls), masters would create stressful scenarios on purpose, like surprise attacks, insults, fatigue drills, etc., to test the student’s ability to maintain inner equilibrium. The goal was to forge an unbreakable Ki, an inner energy that remains balanced and powerful even in chaos.

To the samurai, then, Ki was the secret weapon residing in one’s “heart”. A guide to swordsmanship might remind:

“Ki o mitasu,” fill yourself with energy, for it will give you more action power, a more positive frame of mind, and a stronger impact on others.”

In summary

Achieving this was as important as polishing one’s blade. Through Naiki, warriors learned to ride into battle already victorious in spirit. Their mind like still water, their Ki like a raging current just beneath, and their actions intuitive and decisive. In sum, Naiki unified the invisible and visible aspects of combat and life. The metaphysical and physical. Body, mind, and energy were trained as one. The warrior became a master of himself, which made him formidable against others. This inner doctrine set the stage for more subtle uses of Ki beyond the battlefield, such as perception and communication, which we explore next.

Continues in Part 3…

Your KI article is so in my wheelhouse. It is a fantastic piece. I am looking forward to part 3

As always very insightful 😊