Bushidō throughout history

Disclaimer: The content I will be sharing here may challenge pre-existing notions about Bushido for some readers. However, I kindly ask you to read this article in its entirety, as it presents unique perspectives that I believe will be interesting and thought-provoking for you.

Hope you enjoy your reading! 🙏

In my observations, I've frequently encountered two contrasting perspectives on Bushidō. The first tends to idealize it as a revered code adhered to by all samurai long before the Tokugawa period (1603–1868). The second perspective starkly rejects this notion, dismissing Bushidō as a poetic and melodramatic creation fabricated for political indoctrination. For instance, many historians claim that during World War II, many soldiers were influenced by an ideology linked to the Bushidō code, encouraging acts of self-sacrifice on a massive scale, as seen in the phenomenon of the suicidal "Kamikaze."

I hold the belief that the truth lies somewhere in between these extremes. While it is accurate that there are no historical records of the term "Bushidō" being used before the Edo Period, that doesn’t mean that this idea was inexistent. Its prominence was largely reinforced by Inazo Nitobe's book titled "Bushido: The Soul of Japan." In this influential work, Nitobe outlines the principles of Bushidō, listing seven main principles. In my perspective, I would include an eighth principle from the same book: overcoming the fear of death.

The notion of transcending the fear of death and committing one's life to the path of the warrior is frequently encountered in the book "Hagakure," believed to have been written between 1709 and 1716.

It's crucial to recognize that the Bushido presented in Nitobe's book largely reflects his perspective and is primarily associated with what I'd term Modern Bushido. While I appreciate and find value in reading it, I want to emphasize that this interpretation differs significantly from the ethos followed by the Bushi (Warrior) —the term historically used more than Samurai—in the feudal periods.

This is the natural course of things, as many philosophies, ideas, and concepts undergo evolution over time. While human minds may tend to solidify them as they were in a specific period, the reality is that our perception and understanding should adapt to the changing times. It is more meaningful to emphasize the reasons why a philosophy is applicable rather than simply copy-pasting it from a specific era.

For what’s more, the majority of the wars at that time were as pragmatic as they could be, focusing on winning on whatever means possible.

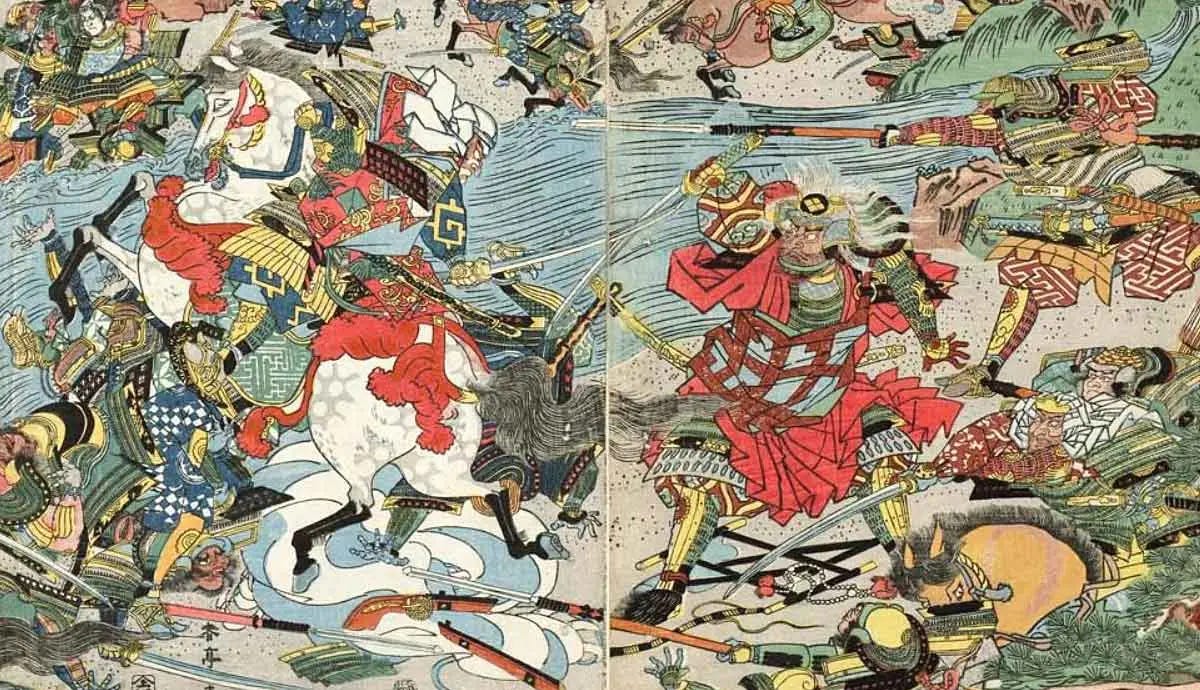

Battle of Kawanakajima - Print, 1857

In the periods of conflict such as the Sengoku Jidai / Warring States Period (1467-1568) and Imjin Wars / Korea Invasions (1592–1598), numerous samurai engaged in actions that deviated from honorable conduct. Contrary to common perceptions, many samurais shifted allegiances during the Sengoku period, displaying opportunistic behaviors, though exceptions existed. The Imjin Wars witnessed numerous massacres and atrocities against civilians in places like Busan and Jinju. When Hideyoshi issued orders to massacre the Korean civilian population, a significant number complied without hesitation. However, it would be inaccurate to portray all samurais as bloodthirsty monsters; Korean records indicate that some samurais halted the killing once they fulfilled a predetermined quota. Similarly, certain Daimyos conducted themselves with dignity, working to end the war, while others took pleasure in the bloodshed and conquest.

Also, let’s take into consideration the principle of Honor. The definition of "honorable" depended on the context. For some samurai, honor was synonymous with serving their Daimyo (a lord or master), and whatever the daimyo deemed honorable, the samurai would also consider as such. Instances exist of samurai who were deemed "honorable" but engaged in reprehensible acts, such as killing their own family to demonstrate loyalty.

In essence, every samurai adhered to their version of "honor," but the interpretation varied among individuals and was not universally consistent. Thus, as with all human beings, the moral values of samurai varied from individual to individual, and underwent some changes through the centuries.

Nevertheless, there are accounts of samurai who sacrificed their lives for a noble cause, embodying the values associated with the Bushido we know today:

The story of the 47 Ronin

The 47 Ronin

One is the famous story of the 47 Ronin, which encapsulates the core values of Bushidō, exemplifying loyalty, honor, and persistence. This tale unfolds when these samurai were compelled to commit Seppuku in seeking vengeance for their fallen master.

In 1701, Asano, a daimyo representing the Ako region, was insulted by Kira, a powerful official from the Tokugawa shogunate, during a visit to Edo castle. The provocation stemmed from Asano's failure to bribe Kira. Overwhelmed by insults, Asano lost his temper and assaulted Kira, resulting in the shogunate condemning him to immediate seppuku, executed on the same day.

Undeterred by the consequences, Asano's 47 loyal men pledged to avenge their master, fully aware that retaliation against Kira would lead to their own execution. Constantly surveilled by Kira's spies, the masterless samurai leader spent time in Kyoto, notably visiting the Ichiriki Chaya Geisha House on Hanamikoji Street. After a year and a half of strategic planning, the 47 ronin executed their plan, capturing and avenging their master by employing the same method used for Asano's seppuku. Accepting the inevitability of their fate, they turned themselves in, and the government mandated their collective Seppuku (Harakiri).

To preserve the samurai bloodline and relay the events in Edo to the people of Ako, the youngest ronin was spared.

The death of Kusunoki Masashige

This is a photo I took at Kusunogi’s statue when I was in Tokyo.

Kusunoki Masashige's story unfolds against the backdrop of political upheaval in medieval Japan. Emperor Go-Daigo, seeking to restore imperial authority and diminish the power of the Kamakura shogunate, turned to Masashige. Known for his tactical brilliance and commitment to the emperor, Masashige became a key figure in the resistance against the Ashikaga shogunate, which had risen to power in opposition to the imperial court.

The pivotal moment in Masashige's life occurred during the Battle of Minatogawa in 1336, where he faced the overwhelming forces of Ashikaga Takauji. Despite being vastly outnumbered, Masashige devised a strategic defense, making the most of the challenging terrain. His warriors fought valiantly, but in the end, they could not withstand the relentless assault. His final resolve was to secure time for the emperor to get into safety, and not fall into enemy hands. In the end, Masashige chose an honorable death over surrender by committing Seppuku.

After the establishment of the Ashikaga Shogunate, he has deemed as a traitor, but during the Edo period, this changed. At that time, Scholars and Samurai were influenced by Neo-Confucian theories, giving rise to new ideals. A new legend about Kusunogi emerged, embodying virtues such as loyalty, courage, and devotion to the emperor.

True, as we witness in many pages of history, history is written by the victor, and the symbol of Kusunogi Masashige was further used during World War II to indoctrinate solders towards suicide missions and extreme self-sacrifice. However, despite all this, Masashige’s actions were something out of the ordinary, and close to the ideals of Bushidō.

I could go on with other examples throughout history, but I think for the time these examples are enough.

3 main eras of Bushido

In his book on BUSHIDO, Alex Bennett highlights three distinct historical periods in the evolution of Samurai ideals, each marking a transformation in the meaning of Bushido:

The pre-1600 era, characterized by a warrior ethos shaped in a context of continual warfare. It's essential to note that during this period, the term "Bushido" had not yet come into existence.

The philosophical development of Bushido during the Edo period (1603–1868), primarily influenced by Confucian and military scholars. This era, marked by relative peace, saw a shift in the warrior spirit towards self-cultivation for the maintenance of social order.

This is the period where Hagakure, the book of the Samurai, was written (between 1709 and 1716) by Yamamoto Tsunetomo.

The modern reinterpretation of Bushido in the Meiji period (1868–1912) and beyond, representing a significant transformation of Samurai culture as part of the formulation of a new Japanese national identity. Even today, many Japanese people associate Bushido with Japanese-ness, considering it the source of their most noble national traits.

My personal perspective about the matter

Thus far, my emphasis has been on historical events, considering both perspectives mentioned earlier. Moving forward, I aim to share reflections derived from extensive readings of historical books and my study in human psychology. Here, I present my conclusions in a list:

1. While the concept of Bushidō found its expression in Japan, its essence is as ancient as human history itself.

One of my favorite teachings from Miyamoto Musashi's Book of Five Rings is the notion of perceiving that which cannot be seen with the eye. I interpret this lesson to extend beyond the area of combat, serving as a philosophy for life in general. Concerning Bushido, what is exaggerated by cinema and pop culture is what is readily visible to the eye. However, the true essence of Bushido lies beneath the surface.

Musashi, in his Wind Scroll, strongly advised against becoming attached to dogma and crystallized forms. Instead, he emphasized the importance of grasping the essence.

The idea of Bushidō, the Way of the Warrior in Japan, goes beyond just one culture and has roots that go back in time. The values of Bushidō, like loyalty, honor, and self-discipline, are similar to ethical codes in other cultures. For example, in Confucianism, the emphasis on moral rectitude, loyalty, and benevolence mirrors the virtues upheld in Bushidō. Even the ancient Egyptians had a concept called Maat, which focused on justice, truth, and balance, showing similarities to Bushidō.

Various warrior groups across the globe, including the Native American Warrior Tribes and the medieval European knights, embraced concepts such as bravery, honesty, and a sense of duty, similar to Bushido. History, as it often does, repeats itself, and in the history of knights, a majority operated as mercenaries without a defined code of conduct. Nevertheless, akin to Japan, there are tales of a minority among them who lived a life of self-sacrifice in alignment with the Way of the Warrior.

Also, in Chinese philosophy, the connection to the Tao reflects the universal aspect of Bushidō. The idea of aligning with the natural order in Taoism is similar to Bushidō's idea of being in harmony with the world. By seeing these common themes in various cultures, Bushidō shows itself as a timeless and global way for people to seek moral guidance and live honorably.

Even in my homeland, there is a warrior from the IX century who sacrificed his life by placing his chest in front of a cannonball before firing. His intention was to make the cannon collapse, providing more time for his comrades to prepare a counterattack.

I can provide numerous examples throughout history, and that fundamental essence will persist despite its adaptations to cultural and period contexts.

2. Just because there was a minority of Samurai that embodied the values of Bushidō, that doesn’t mean that those values were not present.

Just because there was a minority of Samurai that embodied the values of Bushidō, that doesn’t mean that those values were not present. Moreover, just because the term Bushidō wasn’t explicitly used, that doesn’t negate its underlying influence, even though the majority did not live according to it.

The Samurai, often romanticized as epitomes of martial virtue, were not a homogenous group in their adherence to Bushidō. While some warriors fervently embraced the ethical code, others navigated the complex socio-political landscape with a more pragmatic approach. The presence of a minority committed to Bushidō, however, serves as a testament to the enduring appeal of its principles, even in the face of divergent paths.

It is crucial to recognize that Bushidō was not a rigid set of rules etched in stone but rather a fluid philosophy shaped by the socio-cultural context of feudal Japan. The absence of an explicit term does not diminish the existence of its core tenets, which found expression in various forms across different regions and clans. The unwritten code of conduct emphasized virtues such as rectitude, courage, benevolence, respect, honesty, honor, and loyalty. These principles, whether explicitly acknowledged or not, left an indelible mark on the moral fabric of the Samurai class.

The majority of Samurai may not have overtly lived according to the tenets of Bushidō, as the turbulent times often demanded pragmatic choices and adaptability. Economic pressures, political instability, and the ever-changing dynamics of war frequently forced warriors to prioritize survival over adherence to an idealized code. Yet, beneath the surface, the spirit of Bushidō lingered, influencing individual decisions and shaping the broader cultural ethos.

A Japanese proverb with enduring wisdom advises, "Give salt to your enemies." This saying became ingrained in the Japanese vernacular following an incident involving Uesugi Kenshin, a formidable daimyo from the 1500s who governed the province of Echigo (modern-day Niigata Prefecture). In a notable gesture, Uesugi provided salt to his longstanding rival, Takeda Shingen, ruler of the province of Kai (modern-day Yamanashi Prefecture). The act was prompted by a blockade on Takeda's salt supply from neighboring lands. Uesugi proclaimed, "Wars are to be won with swords and spears, not with rice and salt."

The story is often cited as an example of the bushido code of honor prevalent among samurai during the Sengoku period. Despite being fierce adversaries on the battlefield, Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin were able to set aside their differences temporarily for the greater good of their respective domains.

A painting of Uesugi Kenshin against Takeda Shingen clashing.

In examining the historical record, one must resist the temptation to oversimplify the role of Bushidō in the lives of Samurai. The minority who embodied its values were torchbearers of a cultural legacy that persisted despite the challenges of their time. Their commitment serves as a reminder that ideals, even when embraced by a few, possess the power to transcend generations and leave an enduring impact on a society's collective consciousness.

In conclusion, the absence of a universal adherence to Bushidō among the Samurai does not negate its presence in the cultural landscape of feudal Japan. The minority who upheld its principles acted as guardians of a moral compass, ensuring that the essence of Bushidō endured, influencing the trajectory of Japanese history in ways both seen and unseen.

Probably when Yamamoto Tsunetomo wrote Hagakure, the Book of the Samurai, more than a 100 years latter, he took into consideration these particular examples by seeing them from a philosophical perspective.

3. The difference between THE ART OF WAR and THE WAY OF THE WARRIOR

In the world of martial philosophy, two important concepts, "The Art of War" and "The Way of the Warrior," serve as guiding principles for those wanting to grasp its essence.

While both address the challenges of warfare, they diverge in their essence and application, shedding light on the nuanced relationship between external strategy and internal transformation.

Let's be honest – in times of war, where survival is on the line, the instinct for self-preservation often takes precedence, making it challenging for most individuals to adhere to a moral code. The harsh realities of the battlefield demand adaptability and strategic prowess, sometimes overshadowing considerations of ethics. It is within this context that we explore the subtle yet profound differences between Sun Tzu's "The Art of War" and the broader concept encapsulated by "The Way of the Warrior."

From my understanding, "The Art of War" is more a skill that is expressed in action, predominantly outward. Sun Tzu's classic treatise on military strategy is a pragmatic guide that emphasizes tactics, maneuvering, and adaptability in the face of conflict. It acknowledges the harsh realities of war, recognizing that victory often lies in exploiting weaknesses, understanding the terrain, and outmaneuvering the adversary. In essence, it is a handbook for success on the battlefield, irrespective of the moral standing of the participants.

Conversely, "The Way of the Warrior" transcends the external manifestations of warfare; it is an inner process that extends beyond the realm of physical combat. Rooted in traditional martial arts philosophy, "The Way of the Warrior" involves not only the external training of a warrior in skill but also the internal journey of self-discovery and self-mastery. The warrior, in this context, confronts and overcomes his most formidable enemy – himself. It is a path that intertwines physical discipline with ethical considerations, forging a holistic approach to personal and spiritual development.

While "The Art of War" is a strategic blueprint applicable to a broad spectrum of conflicts, "The Way of the Warrior" delves into the profound depths of personal transformation. The warrior, in embracing this path, seeks not only victory on the battlefield but also mastery over the internal struggles that define his character.

During the Warring States period, it can be argued that the "Art of War" held more influence than the inward-focused "Way of the Warrior." As the situation gradually became more stable during the 17 century, the internal martial aspects of the "Way of the Warrior" became more prominent, leading to increased mentions of Bushidō . As mentioned earlier, when survival is at stake, many people turn to the practical strategies of the art of war, while a few are willing to sacrifice their lives for their ideals—a recurring theme in history.

Some suggest that Bushidō was invented during the peaceful 17th century when there were no wars, and the Samurai class had little to do. However, I don’t completely agree with this claim. The Samurai had much too do during that time as well. Firstly, there were numerous rebellions during that time. Secondly, many dojos and martial competitions were established to keep the warrior class active. Thirdly, despite the apparent restriction of weapons to commoners, an underground world of crime allowed individuals from other classes to possess weapons and train in martial skills. Therefore it’s true that the Warring States period was over, but still those times were not entirely characterized by tranquility.

4. Even though the essence of Bushidō stays the same, its form adapts with time.

I believe that a fundamental aspect leading one to the path of Bushido is the idea of "fighting for." In contrast, the emphasis in the Art of War is on "fighting against." The Art of War comprises a set of material and psychological skills and resources aimed at defeating external adversaries.

Bushido is a psychological and, perhaps, a spiritual path where individuals fight for various reasons. This can range from self-expression and overcoming inner adversaries to dedicating one's service to a larger ideal, whether it be family, a specific community, or a cause.

The Art of War serves as a tool to fulfill the purposes of the ego. That doesn’t mean that the Art of War is bad, or that the Edo is bad. It’s part of us, and it’s there for a reason. On the other hand, the Way of the Warrior centers around a transpersonal commitment—a commitment to something far greater than one's individual ambitions. Those following the Way of the Warrior view their own self-improvement and inner growth as contributions to the greater good of society. The more virtuous and internally strong a warrior becomes, the more they have to offer to the collective well-being.

In today's world, where we operate and make daily choices from both ego-driven and altruistic perspectives, it is essential to cultivate both external and internal aspects—both the means of the Art of War and the inner work of Bushidō.

A balanced personality develops equilibrium between their Art of War and their commitment to Bushido. A person dedicated to strengthening their character naturally recognizes the need and wisdom to cultivate virtues such as courage, honesty, sincerity in expression, the instinct of eternity, altruism, and all that reflects the principles outlined in Inazo Nitobe's book, Bushido. In reality, we don't blindly adhere to a set of principles to align with Bushido. When we wholeheartedly dedicate ourselves to Bushido, we naturally find the will to cultivate and express these virtues—a beautiful and noble aspect of human beings that transcends the darker times in history.

This embodies the essence of Bushido. Although the outward expression of this essence may adapt and evolve over time, its core remains unchanged. Centuries ago, individuals had to make life-altering sacrifices to ensure that something dear would endure, as failure to do so could result in the loss of everything and everyone anyone.

Today, the form of sacrifice has transformed; these drastic, life forfeiting measures are no longer necessary. Instead, our self-sacrifice takes the form of stepping beyond our individualistic comfort zones, investing extra time, or enduring sleepless nights to care for our family, children, friends, or any cause that contributes to the greater good.

Rather than physically laying down our lives, we symbolically slay ourselves by conquering our vices and emerging stronger. Modern courage is exhibited not in battles against rival samurai but in pursuing our heartfelt inspirations, delivering presentations despite fear, competing in various fields despite insecurities, and more.

Our integrity and sincerity in expression manifest in resisting the temptation to conform to trends merely out of fear of non-acceptance. Instead, we find the inner strength to stand for our beliefs without shame.

While today's modern Bushido may not present the same challenges as that of samurai from centuries ago, we still have a Way of the Warrior to follow, complete with the unique challenges of our times. Let us continue to fight the good fight!

🙏 Appreciate you for reading

If you enjoy my Pen and Sword Journal writing, you can show your support in various ways without any cost by subscribing, liking this post, leaving a comment if you have thoughts to share, or simply sharing it with anyone who might find it interesting.

By subscribing for free, you will receive every week an article the covers topics about warrior psychology and philosophy like this one.

Alternatively, if you wish to contribute more significantly and help sustain the continuous research and daily content creation, you can become a paid supporter of Pen and Sword Journal at just $5 per month.

What you get by becoming a paid supporter is access to extra members-only essays, such as “Mushin 無心: The Samurai Alternative”, or “STRIKE FIRST: Exploring the Strategic Application of a Seizing-The-Moment Mindset”, access to all the archive, as well as an opportunity to recommend topics for future essays.

Your generous contribution means a lot to me, because diving deeper into warrior psychology and human potential is my passion and one of my life purposes, and your support enables me to devote more time to researching and writing high-quality content regularly.

🔻📕Additional Resources:

If you've found the philosophy of the warrior spirit inspiring and want to delve deeper into this subject, I recommend checking out my book, "100 Thoughts for the Inner Warrior."

Whether you're seeking personal growth, to fortify your inner strength and mental resilience, or simply a deeper understanding of the warrior ethos, "100 Thoughts for the Inner Warrior" is a valuable resource that can guide you on your journey. You can find more information about the book and how to get your Paperback or Kindle copy here, and if you like the Hardcover version, you can get it here.

👉 Furthermore, you can consider joining my WhatsApp channel via this link if you don’t want to miss future updates.

Much respect! 🙏

Great insight, as always. Appreciate your work and really enjoyed this perfectives regarding Bushido!